“Like Patenting the Sun”: America’s Fight Against Polio and the Power of a Vaccine

May 14, 2025

In the early 1950s, as the United States relaxed in the post-WWII glow, a terrifying disease threatened to disrupt the safety and peace that families had fought so hard to secure. Polio, a virus that cast a shadow over families for decades, surged to alarming levels, with a peak of 57,879 reported cases in 1952, resulting in 3,145 deaths. This terrifying epidemic, which primarily struck children, shattered the idealized vision of suburban life and posed an existential threat to the very idea of family safety in a modern, scientifically advanced world.

A Nation Gripped by Fear

For middle-class American families, polio was an unwelcome intrusion into a life they believed they could control. The postwar years had promised safety—victory over the Great Depression, success in World War II, and the newfound comforts of suburban living. But polio, which could paralyze or kill seemingly without reason, introduced a sense of vulnerability and helplessness. The random nature of its spread left families in constant fear. An otherwise healthy child could be struck down in an instant, leaving parents to wonder where they went wrong.

The polio virus could take anywhere from six to twenty days to incubate and remained contagious for up to two weeks. Its long incubation period, coupled with the fact that the virus was highly stable in the environment, made it nearly impossible for experts to track how it was spreading. Some believed it was spread through water, leading to public pools and beaches being closed during the summer months. In fact, one book about the epidemic is aptly titled The Summer Plague, emphasizing how the virus seemed to return each year, adding to the dread.

The Impact of Polio on Daily Life

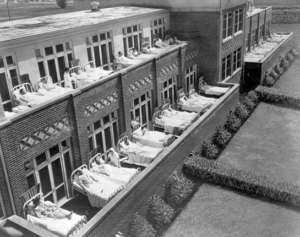

During the height of the epidemic, life as usual was put on pause. Swimming pools, movie theaters, and even playgrounds were shut down to protect children from the virus. Parents, gripped by the fear that their children could “catch polio” at any given moment, kept them isolated, away from friends, and away from public spaces. Rumors abounded, blaming soft drinks, weather patterns, or even the use of paper money for spreading the disease. Health officials, overwhelmed by the unpredictability of the virus, took extreme measures—such as isolating children suspected of being infected and quarantining them in sanitariums.

By the time the polio epidemic reached its peak, fear was ingrained into American life. Each summer, when the virus was most active, the country seemed to hold its breath, waiting for the next wave of infections.

Counterintuitive Culprit: Hygiene and Clean Water

Polio had existed in obscure forms before the twentieth century, with occasional outbreaks in the 18th and 19th centuries. But it wasn’t until the early 1900s that the disease became a widespread epidemic. The clue to its terrifying rise was hidden in something presumably beneficial: improving sanitation and clean water systems. Before the 20th century, the virus was rampant in water supplies. When a very young child was exposed, it would often cause a mild reaction, such as diarrhea, that would lead to lifelong immunity.

But as public health efforts improved sanitation and water systems, children no longer had the mild exposure that would naturally build immunity. As a result, polio began to affect older children and young adults who were not immune. With no understanding of the virus’s transmission or how to prevent it, epidemics like the one in 1916, and later ones in the 1940s and 1950s, were disastrous. Polio’s victims were disproportionately from the middle class, which struck fear into this emblem of American global superiority. The virus struck at a time when modern society had assumed it had mastered infectious diseases. Polio was the cruel reminder that not even the most advanced systems could protect against everything.

The Search for a Vaccine: A Triumph of Science and Collaboration

In the midst of this public health crisis, hope emerged in the form of a vaccine. Dr. Jonas Salk, a name now synonymous with polio eradication, developed the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), which would change the course of history. By 1955, the vaccine had been tested and found to be both safe and effective. This was a monumental breakthrough. For Salk, the success of the vaccine was not about personal profit—he famously refused to patent it, saying it would be like “patenting the sun.”

The introduction of the vaccine led to a massive public health campaign. Between 1955 and 1962, over 400 million doses of the vaccine were distributed, dramatically reducing cases by 90%. Polio, once the most feared disease in America, began to fade into memory. The collective effort that brought the vaccine to fruition—through the leadership of President Franklin Roosevelt, the work of scientists like Salk, and the bravery of volunteers who tested the vaccine—was a triumph of cooperation and public trust in science.

The Cold War Twist: The Sabin Vaccine and Global Cooperation

While Salk’s vaccine was taking hold in the U.S., another breakthrough emerged. Dr. Albert Sabin developed an oral polio vaccine, which could be taken in a simple pill rather than requiring an injection. However, by the time Sabin was ready to test his live-virus vaccine in the U.S., many children had already received the Salk vaccine, so he turned to Eastern Europe for testing. In one of the most remarkable stories of Cold War collaboration, Sabin tested his vaccine on millions of children in the Soviet Union, Hungary, and other Eastern European countries, where the results were overwhelmingly positive.

The success of the Sabin vaccine in these countries demonstrated the power of international cooperation during a time of immense political tension. Hungary, in particular, became a pioneer in polio vaccination, beginning its nationwide vaccination campaign in 1959—four years before the United States adopted the Sabin vaccine. This global effort to eradicate polio marked a rare moment of unity in an era defined by the ideological divide of the Cold War.

A Faint Memory: Polio’s Legacy and the Ongoing Struggle

By the end of the 20th century, the specter of polio had receded into the background of public consciousness. With vaccination programs and public health campaigns, polio became a disease of the past in many parts of the world. However, the legacy of this disease lives on, not only in the memories of those who lived through the epidemic, but also in the ongoing fight to eradicate it completely.

In some ways, polio is now a victim of its own success. Today’s parents, who have never seen the disease’s devastating effects, may take vaccines for granted. But the history of polio serves as a reminder of the power of science, collaboration, and public trust. It also underscores the importance of remaining vigilant in the face of new and evolving health threats.

References

Janssen, Volker. (2023). When Polio Triggered Fear and Panic Among Parents in the 1950s. Retrieved from https://www.history.com/news/polio-fear-post-wwii-era

Kurlander, Carl. (2020). How the deadly polio epidemic changed American life for decades before a vaccine was found. Retrieved from https://www.milwaukeeindependent.com/syndicated/deadly-polio-epidemic-changed-american-life-decades-vaccine-found/

Lienhard, John H. Polio and Clean Water. Retrieved from https://engines.egr.uh.edu/episode/1527

Rochford, Rosemary. (2022). A virologist explains polio’s history as fears of a resurgence grow. Retrieved from https://arkansasadvocate.com/2022/09/08/a-virologist-explains-polios-history-as-fears-of-a-resurgence-grow/

Vargha, Dóra. (2018). Polio Across the Iron Curtain: Hungary’s Cold War with an Epidemic. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK565345/

Weeks, Linton. (2015). Defeating Polio, The Disease That Paralyzed America. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/npr-history-dept/2015/04/10/398515228/defeating-the-disease-that-paralyzed-america